My

philosophy is that if the time

has come, the time has come. My

philosophy is that if the time

has come, the time has come.

-- Hermann Goering at

Nuremberg.

-- Hermann Goering at

Nuremberg.

|

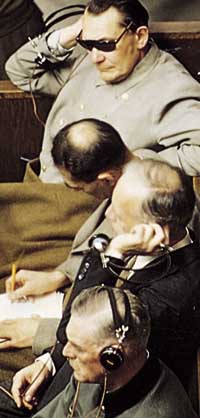

Picture

added by this website; from

David

Irving: Nuremberg, the Last

Battle

Tuesday, February 12, 2002

Why I

have a sneaking sympathy for Milosevic

By Robert Harris (Filed:

12/02/2002)

I FEEL vaguely ashamed

to write the sentence that follows, but

here goes. I have come to feel a sneaking

sympathy for Slobodan

Milosevic.

I know, I know - you don't have to tell

me. The man is wicked and cynical, almost

beyond belief. He bears the largest share

of the responsibility for a series of

"small" wars that killed more than 200,000

people and traumatised millions more. If

he died tomorrow, I wouldn't care. It was

surely a pity for humanity that he was

ever born.

Yet still, as he is led into the dock

at The Hague this morning, to begin a

trial for war crimes that is expected to

last until 2004, some obscure part of me

will be hoping he makes a fight of it,

just as I have found his earlier defiance

of the court oddly compelling.

When he was asked at a previous hearing

for his opinion of its procedures, and

when he retorted, folding his arms,

"That's your problem!", I found myself

thinking, "Well, yes, actually: good

point." Monster he might be, but the

sheer, contemptuous resilience of the man,

in the face of world opinion, commands an

uneasy respect.

We have been here before. Milosevic, as

we are regularly reminded, is the most

senior figure to be arraigned before an

international tribunal since Hitler's

number two, Hermann Goering

(right) at

Nuremberg in 1946, and the way the two

cases are developing is curiously

similar.

Like Milosevic, Goering was in poor

shape, physically and psychologically,

when he was first arrested, but prison had

a restorative effect. He was detoxified,

slimmed down (he lost nearly six stone),

and on the eve of the trial recorded an IQ

of 138. Too late, the Allies realised the

problem they had created.

Like

Milosevic, Goering's strength,

paradoxically, was the hopelessness of his

position. He was in no doubt about the

nature of the proceedings facing him. This

was a hearing with only one possible

outcome. (The prosecutors in The Hague, of

course, hotly deny that theirs is a "show

trial", but does anyone seriously suppose

that Milosevic will walk free at the end

of the next two years?) Like

Milosevic, Goering's strength,

paradoxically, was the hopelessness of his

position. He was in no doubt about the

nature of the proceedings facing him. This

was a hearing with only one possible

outcome. (The prosecutors in The Hague, of

course, hotly deny that theirs is a "show

trial", but does anyone seriously suppose

that Milosevic will walk free at the end

of the next two years?)

A court of justice is a theatre; the

trial is the play. Once an accused ceases

to act the role in which he is

traditionally cast - ie, once he stops

trying to save his own skin - the drama

necessarily takes on a different form. "My

philosophy is that if the time has come,

the time has come," Goering told his

defence counsel before he took the

stand.

"Accept responsibility and go down with

guns firing and colours flying! It's the

defence of Germany that is at stake in

this trial - not just the handful of us

defendants who are for the high jump

anyway."

And so, for several, deeply

embarrassing days, Goering cheerfully ran

rings around the high-minded, flat-footed

American prosecutor, Robert H

Jackson. Like Milosevic, Goering had a

certain rough and cynical charm; restored

to prime condition, broad-shouldered and

deep-voiced, he exuded a powerful

presence.

Like Milosevic, he also had a

reasonable command of English, but chose

not to reply to questions until they had

been translated into his native tongue - a

useful advantage during cross-examination,

allowing him time to phrase his

replies.

Above all, he played on the nature of

the court's proceedings to portray himself

as the object of "victor's justice".

Perhaps his most telling reply to the

hapless Jackson

(left) came

when the American produced a 1935

document, outlining German plans to clear

the Rhine of civilian river traffic in the

event of mobilisation: wasn't this,

demanded Jackson, a secret blueprint for

war?

"I do not think I can recall,"

responded Goering, "reading beforehand the

publication of the mobilisation plans of

the United States."

As

Airey Neave, a British intelligence

officer who interrogated Goering at

Nuremberg, ruefully recorded 32 years

later: "No one had been prepared for his

immense ability and knowledge. As

Airey Neave, a British intelligence

officer who interrogated Goering at

Nuremberg, ruefully recorded 32 years

later: "No one had been prepared for his

immense ability and knowledge.

"No one had realised how much his

strong character and ruthlessness had been

restored by months in prison. Murderer he

may have been, but he was a brave bastard

too."

Similarly, no one knows how Milosevic

will perform in the coming weeks and

months. He might try to make long speeches

from the dock, a la Goering, inviting the

judges to switch off his microphone, as

they have done before.

He might try to call such witnesses as

Bill Clinton, Tony Blair and the

former Secretary-General of Nato,

Javier Solana (they won't come, we

may be sure, but the point will be made -

this is an unfair hearing).

He might try to muddy the waters by

demanding to know why the deaths and

destruction resulting from the allied

bombing, or the activities of the Croats

and Muslims, aren't also being taken into

account. He might, conceivably, say

nothing at all.

Goering, in the end, was destroyed by a

clear chain of evidence linking him to

one, relatively minor atrocity in the

great catalogue of horror from the Second

World War: the execution of 55 RAF

officers who had escaped from a Berlin

prisoner of war camp in 1944.

It is possible that something similar

will happen to Milosevic - that it will be

some small, terrible, single incident,

rather than these huge, generalised

"crimes against humanity" of which he is

accused, that will puncture his bravado

and secure his inevitable conviction.

But between now and then, I wouldn't be

surprised if Milosevic - lonely, defiant,

fighting against the odds - wins some

unlikely international sympathy. The

British at the end of the Second World War

wanted to shoot all the senior Nazis such

as Goering out of hand; it was the

Americans who insisted on a trial.

Today, with Milosevic, the roles are

reversed: the British want the trial; the

Americans are uneasy about the

embarrassments it might throw up. It could

prove that they have a shrewder

appreciation than we do of the perils of

the Goering Syndrome.

A related and highly recommended

article, "Victor's

Justice", has also been published

in The Spectator.

A related and highly recommended

article, "Victor's

Justice", has also been published

in The Spectator.

|