|

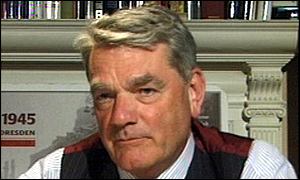

London, April 17, 2000 It took 62 days in court and more than 36,000 pages of evidence to discredit the historian David Irving. But Mr Justice Gray's verdict, when it came, was a tour de force. He speaks to Clare Dyer

Truth can be an elusive commodity in the courts, and that trial, like most, left many questions unanswered. Libel trials in particular rarely end with the feeling that the full story has been told. Irving v Penguin Books is a rare exception. The painstaking, microscopic examination of historical evidence and the 334-page judgment by Mr Justice Gray have finally put to rest any lingering doubts about the scale and horror of the Holocaust. Yet this result is a by -- product of the narrow task the judge set himself. He is at pains to point out that his role was not to decide what the Nazis did 60 years ago. He did not, therefore -- as Penguin QC, Richard Rampton, did -- make the trip to Auschwitz. His job was to decide whether David Irving had deliberately manipulated and falsified the historical evidence and denied the truth of the Holocaust. "What was at issue -- it can't be said too often -- was Irving's methodology and historiography, but what happened back in the 40's," says Gray. "It wasn't a question of deciding what happened. It's quite difficult to explain why it wasn't necessary to decide what happened. It was a question of seeing what evidence was available at the time and deciding whether the criticisms were justified in the light of whatever evidence was available." He had to look at whether the evidence was that the Holocaust had happened, not whether the Holocaust had actually happened. "If you think about it, it is actually a real distinction." When we meet at 9.30 am in his large, comfortable room in the back corridors of the royal courts of justice Sir Charles Gray is already hard at work on his computer, two weeks into a less remarkable libel case which hasn't made it into the headlines. He can't speak about the issues in the Irving case because it may go to appeal.

"The Tolstoy case was hard," recalls Rampton, "but this [the Irving case] was harder for me. I knew the broad outline but had no idea of the detail. The worst thing for me was to have to go and visit Auschwitz." For Gray, however, the forensic scrutiny of historical evidence distanced the court from the horror of the events. "There was a lot of emotion in Aldington but there wasn't in this because it was all expert evidence and that in a way distanced you from the actual events, which I think is a good thing." He sees a parallel not with the Aldington case but with a completely different type of libel action in which he appeared as a silk. In 1994 he represented the Upjohn company in an action against an emeritus professor of psychiatry, Ian Oswald, over claims that the sleeping pill Halcion had dangerous side effects. That case, which took 62 days in court with exhibits running to more than 36,000 pages, also needed a mastery of complex evidence in an unfamiliar field. In the Irving case, he found it "very revealing" to discover how historians work. "You really examine individual documents very minutely and the use of original source material is extremely difficult and taxing." Had the case been heard by a jury, as most libel cases are, we would have been denied Gray's tour de force, with its damning verdict on Irving as racist, anti-Semitic and a right-wing pro-Nazi polemicist. The jury would simply have found that Penguin had or had not libelled Irving and that would have been that. In the event. both sides agreed the case was too complex for a jury. "I just don't think it could have been fairly tried by a jury;" says Gray; "because the mass of material -- close to 10,000 pages of documents plus books -- was just too big." He was able to produce his judgment quickly by spending two to three hours a day before the court hearings and the same time afterwards summing up the arguments as the case went along. "I think it's very important if anyone wants to read the judgment that they see not only what the findings are but what the arguments were." Having one of the parties represent himself as Irving did, is frequently a judge's nightmare. But Irving was far from a typical litigant in person. No lawyer could have managed such mastery over his material. "He conducted his case in a very impressive way," says Gray. "I really don't feel that he lost out because of not having representation. "Where you've got a litigant in person it's part of the judge's duty to make sure he isn't disadvantaged. I certainly tried and I hope I succeeded in giving him every assistance with technical problems, and I hope he feels he wasn't disadvantaged." Rampton, who appeared against two penniless environmental activists in the long-running McDonalds libel case, agrees that Irving's lack of a lawyer wasn't a problem. "He knows his stuff, does Mr Irving." Rampton says having Gray as his adversary in Aldington v Tolstoy was "the one ray of light" in the case. "He was a wonderful opponent. It was a very hard-fought case. He was a very good advocate and a fair one. I don't think in the whole of that very pressurised trial there was a harsh word between us." Much of Gray's working life has been been spent in the public eye, in one high-profile libel case after another. Apart from Aldington, he has represented Tony Blair's press spokesman Alistair Campbell, the cricketer Ian Botham, the actors Bill Roache and Jason Donovan -- and, yes, he was the weapon Jonathan Aitken wielded against the Guardian, having dispensed with the promised "simple sword of truth". He will not comment on the Aitken case, but is known to have been as gobsmacked as anyone when it emerged that the former Tory minister had told a pack of lies to the court about his stay at the Paris Ritz. George Carman, the Guardian's silk in the case, says: "I'm sure he trusted his client. Who wouldn't, with a man of that background? I'm sure he was both surprised and shocked when he learned his client had committed perjury." At the bar, Carman crossed swords with him in around half a dozen cases, including the action against Channel 4 by journalist Jani Allan over allegations that she had an affair with Eugene Terre'Blanche, leader of the extreme right-wing South African AWB party. In his short time on the bench, say libel barristers, Gray has already shown his judicial qualities. Carman says: "It's very difficult for a judge who hasn't been there all that long to settle down to a case with international implications and deliver himself of such a masterly judgment. It's rare that a libel case has social, political and cultural implications. It was a major challenge of detail and complexity. "I think he has the makings of a very good judge indeed,

and I think that's the view generally of the defamation bar.

He's not an overzealous intervener. He listens very

carefully and doesn't rush in where angels fear to

tread."

| ||||||

April 17, 2000 |