| [All

images added by this website]

London,

Friday, July 11, 2003  Obituaries Obituaries

Lord

Shawcross Prosecutor

at Nuremberg whose brilliant exposition of

the evidence was decisive in bringing Nazi

war criminals to the gallows HARTLEY Shawcross was a

man of commanding intellectual stature,

whose brilliance led him nearly to the top

of a number of different professions -

legal, political, administrative and

commercial. There were those who regretted that he

never quite reached the summit of any of

them. Had his talents been less varied, or

his ambitions more concentrated, he might

well have become - as he was not above

hinting in his memoirs - Lord Chief

Justice, Lord Chancellor or even Prime

Minister. But as he himself wrote, "all my

moves were designed to promote the

happiness and wellbeing of my family,

rather than fame." Nevertheless, as Attorney-General in

the postwar Labour Government, he has his

place in history as Britain's chief

prosecutor at the Nuremberg war crimes

trials of 1945-46. It was there that his

remarkable powers of advocacy were first

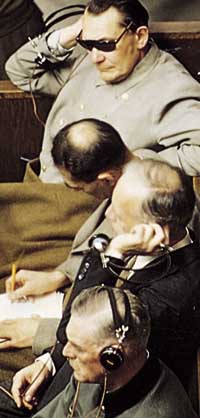

displayed to an international public. The grim, hardly precedented interest

of the trials lay in the spectacle of such

men as Goering, Ribbentrop

and Streicher - who had for so long

been talismans of evil, executants of

crime on a massive scale, yet who had

lived surrounded by power and beyond the

reach of retribution - suddenly being

summoned before the bar of justice by (in

the case of Britain, the United States and

France) the democratic processes of

law.  Of

the Allied chief prosecutors, Shawcross

was adjudged to have performed much the

most effectively. The Russian prosecutor

was continually on the end of the phone

being briefed by his political masters in

Moscow. The American

[Robert H

Jackson, left] was really a

civil lawyer, relatively new to criminal

proceedings and thoroughly out of his

depth. And the French chief prosecutor was

changed after two months, so the French

contribution was inevitably reduced. Of

the Allied chief prosecutors, Shawcross

was adjudged to have performed much the

most effectively. The Russian prosecutor

was continually on the end of the phone

being briefed by his political masters in

Moscow. The American

[Robert H

Jackson, left] was really a

civil lawyer, relatively new to criminal

proceedings and thoroughly out of his

depth. And the French chief prosecutor was

changed after two months, so the French

contribution was inevitably reduced.

It was left to Shawcross to demolish

the defence that the proceedings were

merely "victor's justice". In measured

tones, the more effective for being

entirely without histrionics or anger, he

relentlessly built up the indictment

against the accused of waging aggressive

war in breach of treaty obligations. The

very calmness of Shawcross's exposition

made it the more terrible. He let the

appalling history of Nazi oppression

unfold itself to the courtroom through a

dispassionate relation of facts which told

their own awful story. It was a

performance which gave him an

international reputation.  HARTLEY WILLIAM SHAWCROSS was born in

Germany in 1902, the son of John and Hilda

Shawcross. John, then a lecturer in

English at Giessen University, had been

nurtured on the pure milk of Victorian

Liberalism (his sister married a son of

John Bright); Hilda was a pioneer

in the suffragette and socialist

movements. Shortly after their son's birth

the family returned to England, and in due

course Hartley went to Dulwich College as

a day boy.

HARTLEY WILLIAM SHAWCROSS was born in

Germany in 1902, the son of John and Hilda

Shawcross. John, then a lecturer in

English at Giessen University, had been

nurtured on the pure milk of Victorian

Liberalism (his sister married a son of

John Bright); Hilda was a pioneer

in the suffragette and socialist

movements. Shortly after their son's birth

the family returned to England, and in due

course Hartley went to Dulwich College as

a day boy.

At the age of 16 he spoke and worked

for the local Labour candidate throughout

the notorious Lloyd George "khaki"

election of 1918. After leaving school, he

went to Geneva University with the

intention of becoming a doctor, but he

switched from medicine to law when J.

H. Thomas persuaded him that the

latter discipline was a more convenient

stepping stone to politics. He was called

to the Bar by Gray's Inn in 1925, having

come first out of 220 candidates in the

Bar final examinations.  In

those distant days, getting started at the

Bar was a difficult task for a young man

without influence or private means, and

Shawcross's earnings in his first few

years were as exiguous as those of most of

his contemporaries. In 1927 he accepted a

post as a part-time lecturer in law at

Liverpool University, and at the same time

joined David Maxwell-Fyfe in his

chambers in that city. There he prospered;

he acquired a good mixed practice on the

Northern Circuit, and so was able to give

up his academic work (which was only a

secondary interest) in 1934. In 1939 he

took silk, and in the same year he was

elected a Bencher of his Inn. In

those distant days, getting started at the

Bar was a difficult task for a young man

without influence or private means, and

Shawcross's earnings in his first few

years were as exiguous as those of most of

his contemporaries. In 1927 he accepted a

post as a part-time lecturer in law at

Liverpool University, and at the same time

joined David Maxwell-Fyfe in his

chambers in that city. There he prospered;

he acquired a good mixed practice on the

Northern Circuit, and so was able to give

up his academic work (which was only a

secondary interest) in 1934. In 1939 he

took silk, and in the same year he was

elected a Bencher of his Inn.

When war came, Shawcross, although

enrolled in the Emergency Reserve of

Officers, was unable to join the Forces,

owing to a spinal injury which he had

suffered in a climbing accident many years

before. But he gave up his practice for

the duration, and filled a succession of

public wartime appointments, of which the

last and most important was that of

Regional Commissioner for the North-West.

Here he provided convincing evidence of

his administrative skill and

efficiency. Until he was over 40 Shawcross allowed

his political interest and ambition to lie

fallow; he was too busy earning a living,

and then helping the country's war effort.

But in 1945 he contested St Helens for

Labour, while his younger brother

Christopher took on the neighbouring seat

of Widnes. The brothers fought a colourful

joint campaign, and the lively Shawcross

Express circulated widely over their

section of south Lancashire. They were

both elected with massive majorities, and

arrived at Westminster as members of the

huge block of Labour supporters who had

been returned in the most sensational

electoral upset of the century. Clement Attlee proceeded to form

his Government. The hallowed doctrine of

"Buggins' turn" did not appeal to the

resilient mind of the new Prime Minister,

and when looking for an Attorney-General

he passed over a number of elderly and

rather dusty KCs who must have hoped for

preferment, and chose instead the

43-year-old new MP for St Helens, who

therefore went directly from the hustings

to the front bench, acquiring the

traditional knighthood on the way. Shawcross had already earned a good

reputation in the North West, but he was

still virtually unknown in the capital.

London liked what it saw, for he was

handsome, charming, stimulating and

elegant. It did not, to begin with, so

much like what it heard: his name became

famous overnight when he was reputed to

have said "We are the masters now." In

fact, he never uttered any such phrase -

what he actually said in a debate

repealing the Conservatives' vengeful

Trade Disputes Act of 1927 was "We are the

masters at the moment and shall be for

some considerable time." However, even if

in its authentic form it was intended as a

factual description rather than a boast,

it did Shawcross a good deal of harm. It

was certainly uncharacteristic, for he was

neither a bully nor a zealot; he had

inherited from his parents a sense of

compassion and of caring for the unhappy

and the unlucky, but he was hardly a

fierce party warrior. It quickly became apparent that

Shawcross was an advocate of quite

exceptional calibre. He was cast more in

the mould of Rufus Isaacs than

Edward Marshall Hall. In conducting

his cases he was amiable and even bland.

He smiled readily, and gave the impression

of thinking that everyone in court was

really quite a good fellow, and that the

other side was mistaken or misguided,

rather than wicked. When his

cross-examination was at its most

disruptive, his beautifully modulated

voice (often described as "golden")

remained quiet and polite. He seldom

became angry, and he never aped G. K.

Chesterton's huckster, who, "mocking

holy anger, painfully paints his face with

rage". To his exemplary court manner (and

manners) Shawcross added the power of

lucid exposition, an ability to winnow the

essential from the peripheral, and

tremendous reserves of concentration and

endurance. With this combination of

talents, it was not surprising that he was

soon widely acknowledged as the finest

advocate of his generation.  THE most important duty of the new

Attorney-General was his heavy engagement

in the large number of prosecutions which

followed the Allied victory over Germany.

These were in two categories: of British

traitors and of Nazi war criminals. Among

the former the names of William

Joyce ("Lord Haw-Haw"), Allan Nunn

May, Klaus Fuchs and John

Amery loomed large in the demonology

of the day. Rebecca West, who was

present at all the major treason trials,

was impressed equally by Shawcross's

advocacy and by his character. "He has",

she wrote, "the gentlest and most

charitable of tempers; but he is

fortunate, visibly fortunate. Had Pippa

passed him she would have added him to the

list of proofs that all's well with the

world."

THE most important duty of the new

Attorney-General was his heavy engagement

in the large number of prosecutions which

followed the Allied victory over Germany.

These were in two categories: of British

traitors and of Nazi war criminals. Among

the former the names of William

Joyce ("Lord Haw-Haw"), Allan Nunn

May, Klaus Fuchs and John

Amery loomed large in the demonology

of the day. Rebecca West, who was

present at all the major treason trials,

was impressed equally by Shawcross's

advocacy and by his character. "He has",

she wrote, "the gentlest and most

charitable of tempers; but he is

fortunate, visibly fortunate. Had Pippa

passed him she would have added him to the

list of proofs that all's well with the

world."

Between the earlier and later English

cases, Shawcross went to Nuremberg to

present the British prosecution's case

against Goering, Hess and their

colleagues. This he did in a five-hour

speech which an experienced colleague

described as the most brilliant he had

ever heard, and which was a decisive

element in securing the guilty verdicts.

Although Shawcross was instinctively

against capital punishment, he realised

that at the end of such a trial, with its

relation of such terrible events, any

other sentence would be an anticlimax.

Goering defeated justice by swallowing

cyanide. Ribbentrop and nine others went

to the gallows. Notwithstanding this performance, many

would say that it was in 1948 and 1949, as

counsel for the Lynskey tribunal, that

Shawcross scored his greatest forensic

triumph. This tribunal was set up to

investigate allegations of impropriety

made against certain ministers and public

officials. Shawcross announced that he

would seek the truth "ruthlessly and

relentlessly", and this he did, although

the process necessarily involved much

probing of the actions and motives of

political colleagues and personal

friends. The effectiveness of his exposition and

cross-examination was enhanced by his

calmness: however tense the situation or

however devious the witnesses, he never

became excited or rude. In all his work he

displayed an immense self-confidence which

did not quite topple over into conceit;

rather, it was pride in carrying out

important and difficult duties supremely

well. By 1951 it was clear that Labour's

notable postwar tenure of office was

drawing towards its close. In a final

Cabinet reconstruction in April, caused by

Nye Bevan and Harold

Wilson's resignations, Shawcross

became President of the Board of Trade,

but he had little time to make any impact

in this position, as in the election in

October the Conservatives were returned

and he left office, never to return.  AFTER an absence of more than ten years he

resumed his practice at the Bar, and was

soon reputed to be the highest-paid

barrister in the country. Inevitably,

millionaires jostled for his services,

occasioning a few sour comments from his

former colleagues. He answered these

criticisms with the standard analogy of

the cab on the rank, available for hire by

the first-comer, to which the reply was

made that it was a pity that whenever his

cab reached the front of the rank, the

passenger who jumped in always wore a top

hat.

AFTER an absence of more than ten years he

resumed his practice at the Bar, and was

soon reputed to be the highest-paid

barrister in the country. Inevitably,

millionaires jostled for his services,

occasioning a few sour comments from his

former colleagues. He answered these

criticisms with the standard analogy of

the cab on the rank, available for hire by

the first-comer, to which the reply was

made that it was a pity that whenever his

cab reached the front of the rank, the

passenger who jumped in always wore a top

hat.

Shawcross's days as a keen party man

were over. Opposition did not appeal to

him. "Criticising the other fellow because

he's in and you are not," he said, "seems

to me a futile waste of time." Parliament

had no more enchantment for him, and he

progressively spent less time there, and

more in the courts, and as chairman of the

Bar Council. The nickname that was invented around

this time, "Sir Shortly Floorcross", was

amusing but not entirely apposite. He

accurately described himself as having

become a cross-bencher and, partly perhaps

because there are no cross-benches in the

House of Commons, in 1958 he relinquished

his St Helens seat. In the same year he

retired from practice at the Bar, and in

1959 he was made a life peer. At the age of 56, therefore, Shawcross

entered a new phase of his career. He

became a director of Shell, and worked

hard and travelled widely in the interests

of that organisation. He also joined the

board of many other companies, and for

five years he was chairman of Thames

Television. But he did not entirely abandon his

interest in his two original professions

of politics and the law. In the House of

Lords, in public speeches and in

correspondence in the press, he adopted a

non-party stance, but with a strong bias

towards the maintenance of traditional

values; in the measured and cautious tones

of the elder statesman it was hard to

recognise the ardent crusader who had

fought and won St Helens in 1945. He

maintained his contact with the legal

world by his chairmanship for 16 years of

the organisation Justice. It was inevitable that a man of

Shawcross's capacity and industry, who was

not ostensibly doing a full-time job,

should be asked to undertake various

urgent public duties. Perhaps the most

important of these was the chairmanship of

the Royal Commission on the Press, which

was set up in 1961 after parliamentary

disquiet caused by the sudden and

distressing collapse of the News

Chronicle and Star. Shawcross

guided its deliberations with vigour,

skill and speed, and it was not his fault

(or that of his colleagues) that no

solution to the chronic economic problems

of the industry emerged. When the

commission's report appeared, The

Times described it as "informative,

sensible, taut and unanimous. If it

produces no rabbits out of the hat, it has

shot down some bats in the belfry." In 1969 Shawcross took on another

complex task, the chairmanship of the

Panel on Takeovers and Mergers. He began

by thinking that although the possibility

of misuse of inside information for

personal profit did exist, advantage was

rarely taken of it. But intense study of

the subject convinced him that stern

action was needed to stamp out deals which

involved misuse of privileged

positions. The new City Code, introduced in 1972,

reflected in its main provisions the

anxiety which followed recent

controversial bid tactics. A major change

was the formal introduction of the rule

that the acquisition of 40 per cent of the

voting rights of a company made necessary

a bid to all of the shareholders. In

explaining these recondite matters,

Shawcross pointed out that the duty of the

panel was the enforcement of good business

standards, not the enforcement of law. In 1974, the year that he was appointed

GBE, Shawcross accepted the chairmanship

of the Press Council. He was already 72,

but he had always enjoyed influence and he

hated idleness; it may also be that the

death, not long before, of his second wife

led him to seek solace in unremitting

work. In the event he was to continue to

work for a very long time. As late as 1993

he was regulary attending his office at

Morgan Guarantee Trust in the City. He had been one of the four national

directors of Times Newspapers from the

time the new company was formed in 1966.

He resigned on becoming chairman of the

Press Council, but in 1982, rather

surprisingly (since he was clearly out of

sympathy with its editorial policy), he

became a director of The Observer,

then owned by Lonrho. Shawcross greatly enjoyed the outward

and visible symbols of his success,

including his beautiful period Sussex

house, and, for many years, a capacious

yacht. He was a member of the Royal Yacht

Squadron, the Royal Cornwall Yacht Club

and the New York Yacht Club. He loved

riding as well as sailing. He was a

gracious and charming host, if a shy one.

His abundant public self-confidence was

matched by a certain reserve in his

personal relationships, which were often

based on friendliness rather than

friendship, and companionship rather than

intimacy. He took an active part in the affairs

of the much-loved county where he made his

home. He was associated with Sussex

University from its embryonic stage, and

from 1965 was its Chancellor. He sat on

the council of Eastbourne College (which

was near his home). He was a JP for the

county, and chairman of the Society of

Sussex Downsmen from 1962 to 1975. In his memoirs, Life Sentence,

published in 1995, Shawcross could

look back on a life of exceptionally wide

experience and great achievement. He was

grateful for his good fortune, but

surprisingly harsh on himself. "I know

that in my public life I fell below the

standards that I had set myself," he

wrote. "I have seen what is wrong but not

done enough to put it right. I have been

more critical than correct. I have had

opportunities of great positions in the

service of the state, but I have put them

aside. I know that I have not devoted

myself enough to promoting the good of

others." Probably no one else would have

been so stringent, but nearly 80 years

later he was true to the ideals of the

young campaigner of the 1918 election. Hartley Shawcross was three times

married. First, in 1924, he married

Rosita Alberta Shyvers, who took

her own life in 1943 while suffering from

an incurable illness. In the following

year, firmly advised by his friends to

marry again, he married Joan Winifred

Mather, by whom he had two sons and

one daughter. She was killed in a riding

accident in 1974. Thirdly, Shawcross

married a longtime friend, Mrs Monique

Huiskamp, in 1997. He is survived by

her and by the daughter and two sons of

his second marriage, one of whom is the

writer and broadcaster William

Shawcross. Lord Shawcross, GBE, PC, QC,

Attorney-General, 1945-51, and UK Chief

Prosecutor at the Nuremberg War Crimes

Tribunal, was born on February 4, 1902. He

died on July 10, 2003, aged

101.

David

Irving: Nuremberg, the Last

Battle (free

download)

David

Irving: Nuremberg, the Last

Battle (free

download)

|