Documents on Elie Wiesel | ||||||

Night and the

Holocaust: Things

written, things not written, and things altered --

some observations on the received version of the

Holocaust in the light of Elie Wiesel first book in

non-Yiddish. By Robert

E. Reis, BA, MA This paper is

an analysis of Elie Wiesel's memoir Night

as a piece of historical evidence

regarding the events now described as the

Holocaust. Elie

Wiesel (1928-

) is a French-American author, whose work

addresses Jewish themes, including the

experiences of Jews who suffered in Nazi

concentration camps during World War II.

He won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986 for

his work promoting human rights.. From

1980 to 1986 Wiesel served as chairman of

the U.S. President's Commission on the

Holocaust. he is the author of a well

known book, Night, often prescribed as set

reading for students. According to the

publisher of the 1987 edition,

HarperCollins Canada Ltd, the United

States Library of Congress classifies

Night under the headings "Biography" and

"World War 1939-1945 -- Personal

Narratives, Jewish." This book is not

supposed to be fiction. ELIE Wiesel's famous book

Night was first

published in French in 1958 and in an English

translation in 1960. (All our quotations here are

from the edition contained in The Night

Trilogy published by Hill & Wang, New York,

1987.) It is not suspposed to be fiction. According

to Encarta® Online: "Wiesel's first book,

Night (1958),

describes his experience at Auschwitz. Subsequent

works include many novels and a book of memoirs."

In a 1979 essay, "An Interview Like Any Other," Mr.

Wiesel wrote that he published his memoir La

Nuit after a 10-year vow of silence only at the

urging of Mauriac, whose account of his meeting

with the young survivor appears as a foreword to

"Night's" French and

English editions. [Italics added.] What can we learn about the Holocaust from

Night? Elie Wiesel dedicated

Night to the memory of

his parents and his little sister. Mr. Wiesel introduces us to the horrors of what

will later be called the Holocaust with the story

of Moché the Beadle. In 1942 this man is

deported from Hungary along with many other

non-Hungarian Jews who had been living in the

Hungarian town of Sighet where the Wiesel family

had its home. Several months later he re-appeared

in Sighet and told his neighbours that his entire

transport had been murdered by the Germans after

crossing the frontier into Poland. Nobody believed

him. Mr. Wiesel also tells us that the Jewish people

of his town regularly followed the war news

broadcast from London. Since we know that the

United Press was already distributing charges made

by the World Jewish Congress in London as early as

June 1942 that the Nazis were executing thousands

of Jews each day in Poland and that in December

1942 the allies had issued a joint declaration

condemning Germany's "bestial policy of

cold-blooded extermination," one must assume that

news items like these must have been broadcast from

London to the Jews of Sighet. We also know that In

August 1943, the United Press distributed an

accusation by the Inter-Allied Information

Committee in London that stated the conditions at

Auschwitz were

"particularly severe" and that "58,000 people were

believed to have perished" there. The Jews in the

Hungarian town seems to have ignored or disbelieved

these charges. Mr. Wiesel tells us that as late as the spring

of 1944, in the fifth year of Hitler's wars, the

Jews in Hungary could still obtain emigration

permits for Palestine, but that his father had

refused to sell his business interests in Hungary

and "start from scratch in a country so far away .

. . " Apparently the government of the Regent

Admiral Horthy, the ruler of Hungary, had

been following a rather benign policy toward its

Jewish citizens even though Hungary was allied with

Germany and was contributing troops to the war

against the Soviet Union. In that spring of 1944, with German armies being

pushed relentlessly out of the Soviet Union and the

Allies preparing to land at Normandy, the Regent

accepted the formation of new government led by the

Hungarian fascist party, the Nyilas, and this

government permitted German troops to enter

Hungary. The Nyilas government quickly introduced a

series of increasingly harsh measures aimed at the

Jews: restrictions on movement and employment,

ghettoization, and finally the wearing of the

Jewish star. Much of what Wiesel describes sounds like

organized thievery of Jewish property by the

Hungary fascist police organization. Finally it was announced that the entire

community in which the Wiesels lived was to be

deported. The reason given was that the front had

moved too close to their town. Wiesel tells us that

in fact the Jews in their Ghetto were anticipating

the arrival of the Red Army and the overthrow of

the Hungarian fascist regime. The round-up and deportation was in the hands of

the Hungarian police with the assistance of the

Jewish police that had been recruited by the

elected Jewish Council that had run the ghetto. Instead, the Wiesels entered the cattle cars for

a journey to an unknown destination. It was only after two days, when the train

crossed the frontier into what had been

Czechoslovakia, that German officials took charge

of the transport and the Wiesels realized that they

were leaving Hungary. During these two days, Wiesel asserts that the

young Jews packed eighty to a car with

grandparents, parents, and small children "gave

away openly to instinct, taking advantage of the

darkness to copulate in our midst . . . The rest

pretended not to notice anything." He tells us that one Jewish woman in their

cattle car went insane and screamed over and over

again that she saw "fire" and "flames." First she

was restrained; later she was beaten to

unconsciousness by her neighbours. They arrived at Auschwitz at night. As anyone familiar with the standard histories

of the Holocaust -- Reitlinger, Hilberg,

Dawidowicz -- knows, arriving Jews at Auschwitz

were forced to endure a "selection" by SS-doctors.

We are told that only the healthy Jews were

admitted to the camp in order to become slave

labourers and that the old, the very young, the

infirm, and the women with small children were sent

to the gas chambers. Mr. Wiesel tells us that upon arrival he could

see "flames gushing out of a tall chimney into the

black sky" and that he could smell "an abominable

odour floating in the air." "We had arrived -- at

Birkenau, reception centre for Auschwitz." Perhaps Mr. Wiesel did see flames gushing out of

a tall chimney; however, the sight of flames

gushing from a coal-fired crematorium chimney is

not seen very frequently, or at all, outside of

narratives describing Holocaust crematoria. A

crematorium is not a blast furnace. Mr. Wiesel tells us that he turned on the

reception platform and saw an old man fall the

ground and a nearby SS-man putting away his pistol.

He implies, but does not say that the SS-man had

just shot the old Jewish man. Elie Wiesel was advised by one of the veteran

Auschwitz inmates to say that he was eighteen years

old instead of fourteen; his father was advised to

say he was forty instead of fifty. There is a

strong implication that the inmate believed that

the consequences of being too young or too old

would be dire. The people on the Wiesel transport were asked by

veteran prisoners why they had not hanged

themselves rather than allow themselves to be

deported to Auschwitz. The prisoners were amazed

that the Wiesels -- as late as 1944 -- had never

heard of Auschwitz. This is odd. Elie Wiesel has told us that the

Jews of Sighet had been listening to Allied radio

broadcasts. Walter Laqueur, the Director of

the Institute of Contemporary History in London,

wrote in his 1980 study, The Terrible

Secret, that Auschwitz was "a veritable

archipelago," that "Auschwitz inmates . . . were,

in fact, dispersed all over Silesia, and . . . met

with thousands of people," and that "hundreds of

civilian employees . . . worked at Auschwitz," and

that "journalists travelled in the General

Government [German administered Poland] and

were bound to hear," etc. London had to have had a

pretty good idea about conditions in Auschwitz. After being told by veteran inmates that they

would ultimately be cremated at Auschwitz, some of

the younger Jews wanted to revolt, to escape, to

tell the world about Auschwitz. But they

didn't. The newly arrived Jews from Sighet were first

separated by sex. Dr. Mengele makes his

first appearance in

Night. He is on the

reception platform determining where the arriving

men from Sighet will be sent. He sent Elie Wiesel

and his father "to the left." We are told that a prisoner warned Elie and his

father that going "to the left" meant that they

were being sent straight to the crematory. The

prisoners information was not correct. The Wiesels

were being sent to a reception barracks. Since the men who were sent "to the right" were

all neighbours of the Wiesels and were sharing a

common ordeal with them, it would be helpful in the

evaluation of the credibility of rumours spread by

prisoners to know if the men sent "to the right"

were immediately killed or not. Unfortunately Elie

Wiesel did not discover their fate -- or he has

chosen not to include this information in

Night. On the way to the barracks Mr. Wiesel reports

that he saw flames from a "gigantic ditch" into

which the Germans were dumping babies from a lorry.

"I saw it -- saw it with my own eyes . . . those

children in the flames." And he reports: "A little

farther on was another and larger ditch for

adults." As anyone familiar with the training of

psychiatrists knows, psychiatrist are taught to

suspect dishonesty when a patient voluntarily and

emphatically suggests that something is really,

really true. This is the only time in

Night that Elie Wiesel

insists upon his own veracity in such an emotional

manner. That first night was the night that "has turned

my life into one long night." In the reception barracks the Jews were forced

to strip naked and allowed to retain only their

shoes and their belts and their heads were shaved.

As anyone familiar with the standard histories of

the Holocaust -- again, Reitlinger, Hilberg, and

Dawidowicz -- knows, Jewish prisoners were force to

disrobe and to have their hair shaved off before

they were forced into the gas-chambers. We now

learn from Elie Wiesel that it was the standard

practice to force all new arrivals to disrobe and

to have their hair shaved off. Meanwhile SS officers selected the strongest to

work in the Sonderkommando, the unit that worked in

the crematoria. Then the new arrivals are marched

naked to be disinfected, given a hot shower, and

issued uniforms. But Reitlinger, Hilberg, and Dawidowicz tell us

that the gas-chambers in which the Jews were

exterminated by means of cyanide released from the

crystals of the insecticide Zyklon-B were located

in the cellars of the crematories in Birkenau. The

Jewish men in the Sonderkommando were forced to

live isolated in the crematories and help in the

cremation of the bodies of the people gassed in the

cellars. The gassings themselves are normally

described as an important secret of the Nazis. Mr. Wiesel now tells us that a Jewish man,

Bela Katz, who had been deported from Sighet

the week before and who had been selected to work

in the crematoria managed to get a message to the

newly- arrived prisoners. He tells them that he had

already had to burn the body of his own father.

(About how the elder Mr. Katz died we are not

told.) This event does suggest that the isolation

within which the men of the Sonderkommando are said

to have worked was not always successful in

preventing even a brand new prisoner from

communicating with the prisoners outside of the

crematories. Elie Wiesel and his father were assigned to one

of the barracks formerly occupied by Gypsies at

Birkenau. About the fate of the previous occupants

there is not one word in

Night. This is odd.

Most histories of the Holocaust tell us that the

Gypsy section at Birkenau had been exterminated in

dramatic circumstances order to make room for the

influx of Jews from Hungary like the Wiesels. This

is especially odd since we will soon meet in

Wiesel's book prisoners who had been in Auschwitz

for years. They would have known. Odder still is the fact that Elie Wiesel now

introduces his recollections that a brutal Gypsy

deportee was in charge of the barracks to which he

and his father were assigned and that this Gypsy

knocked Elie's father to the ground with a blow.

Later, ten more Gypsies with whips and truncheons

will escort the new arrivals out of the Birkenau

camp to the separate Auschwitz main camp. It is reasonable to believe that the Gypsies

would have had a powerful interest in knowing the

fate of the rest of the Gypsies at Auschwitz. Yet

there is nothing in

Night to tell us about

the reported extermination of the Gypsy section at

Birkenau. Before being admitted to Auschwitz I, the

original concentration camp at Auschwitz and still

the centre of the administration of the Auschwitz

camp tourist complex, the Wiesels were forced to

take another hot shower. Showers, Mr. Wiesel informs us were "a

compulsory formality at the entrance to all these

camps. Even if you were simply passing from one to

another several times a day, you still had to go

through the baths every time." Mr. Wiesel never

tells us why the Germans insisted on all of this

cleanliness. It seems logical to conclude the shaving of the

hair, the disinfection, and the compulsory hot

showers were hygienic measures mandated in order to

prevent the spread of diseases among the

prisoners. Mr. Wiesel and his father were assigned to Block

17 -- a two-story building made of concrete. Elie

tells us that there were gardens among the

barracks. It was only after being transferred from

Birkenau Camp to the Main Camp that Mr. Wiesel

became prisoner "A-7713." -- his camp tattoo

number. This fact tells us that prisoners only

received an official identity after they had

survived a period of quarantine at the Birkenau

camp and had been assigned to a more permanent

destination within the Auschwitz complex. Here the "Wiesel of Sighet," the author's

father, was searched out by the husband of his

wife's niece, the "Stein of Antwerp." The "Stein of

Antwerp" had been deported in 1942 and wanted news

of the wife and sons he had left behind in Belgium.

The Wiesels had not received any letters from

Antwerp since 1940. Elie Wiesel tells us that he

lied to his relative and told him that his mother

had received news that her niece and the boys were

fine. The "Stein of Antwerp" was grateful for the

news and began sharing his food rations with the

Wiesels. Since the "Stein of Antwerp" had been

deported so long before the Wiesels, and he was

both a Jew and a relative by marriage, he might

have been an excellent source of information about

Auschwitz and what had been happening there.

Whatever he told the Wiesels, it is not in

Night. At the end of the Wiesel's three weeks in the

main camp, a transport from Antwerp arrived. The

"Stein of Antwerp" sought it out for more news. He

never came back to see the Wiesels. Elie and his father were re-assigned to the Buna

Camp, a large chemical factory and concentration

camp that was part of the Auschwitz complex of

camps. German guards marched the Wiesels "slowly"

to the Buna factory camp. There they were required to undergo another hot

shower and they were quarantined for three days

before given any work assignments. Mr. Wiesel does not tell us that the purpose of

the Buna plant was to manufacture synthetic rubber.

The Allies were desperately interested in

information about artificial rubber production

because Japan had over-run much of the rubber

producing territory in the world. Allied

intelligence would have wanted to know what

happened at this crucial German enterprise. Here he tells us that there were children in the

Buna factory camp and that some senior prisoners

gave "bread, and soup, and margarine" to the

children. He adds that some senior prisoners

recruited children for homosexual purposes. Next, a

three-doctor panel gave each new prisoner a medical

and dental examination. "Anyone who had gold in his

mouth had his number added to a list." The Wiesels were assigned to the barracks that

contained the camp orchestra and to a unit of

prisoners that worked in a warehouse for electrical

equipment under the direct command of a prisoner

named "Idek." Standard histories of the Holocaust tell us that

there was an orchestra at Auschwitz that played

music while Jews were "selected" for the

gas-chambers. We are also told that the

gas-chambers were in the cellars of the

crematories. The Buna camp was entirely separate

from the camps in which crematories are known to

have existed. The purpose of an orchestra in the

Buna Camp is not explained in

Night. The musician's barrack was under the supervision

of a German Jew. Each prisoner was issued a

blanket, a wash bowl, and a bar of soap. Since Elie Wiesel had a gold tooth, he had to

deal with a Jewish camp dentist who wanted his

tooth. Soon the dentist was arrested by the Germans

for running a traffic in contraband gold teeth.

Elie kept his gold tooth for a while longer. Since Mr. Wiesel always identifies persons

mentioned in Night by

their nationality and identifies them as "Jewish"

when applicable, it is odd that all of this

information is omitted about "Idek." Since all

standard histories of the Holocaust explain that

the prisoners at Auschwitz always wore emblems on

their clothing that announced their classification

or cause of incarceration: politic prisoner,

conscientious objector, common criminal,

homosexual, etc., and that Jewish prisoners had an

unmistakable emblem sewn on their uniforms; Idek's

Jewishness or lack thereof would have been

immediately apparent to all of the other inmates.

Perhaps the circumstance that "Idek" was engaging

in a consenting sexual relationship with a gentile

girl led our author to omit "Idek's" religion. Mr. Wiesel tells us that the Jewish prisoners

were working along side of non-Jewish prisoners as

well as "civilian workers." The "Idek" incident

shows that the relations between prisoners and

"civilian workers" could lead to intimacies in

which confidence are frequently shared. Soon, Frank, "the Pole," Wiesel's foreman at

work, became aware of the unremoved gold tooth. He

persecuted Elie's father until the boy agreed to

give it up. |

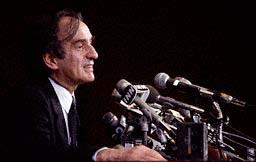

Poseur:

Elie

Wiesel, survivor; author of book:

"Night",

about his horrible sufferings at the hands of the

Nazis; speaking fee: $25,000 per lecture plus

chauffeur-driven car

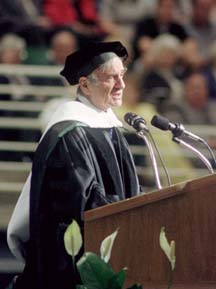

Poseur:

Elie

Wiesel, survivor; author of book:

"Night",

about his horrible sufferings at the hands of the

Nazis; speaking fee: $25,000 per lecture plus

chauffeur-driven car

The

Wiesels were deported in the second transport from

their town. For three days after the first

transport had left, they lived on in a ghetto

awaiting transport. Wiesel tells us that "the

ghetto was not guarded. Everyone could come and go

as they pleased." The Wiesels even refused an offer

from a former Gentile servant to hide them in her

village. Despite listening to the broadcasts from

London, it is clear that the Jewish population of

Sighet had never heard or never seen any reason to

believe that Germany and its allies were following

a policy of physically exterminating the Jews of

Europe.

The

Wiesels were deported in the second transport from

their town. For three days after the first

transport had left, they lived on in a ghetto

awaiting transport. Wiesel tells us that "the

ghetto was not guarded. Everyone could come and go

as they pleased." The Wiesels even refused an offer

from a former Gentile servant to hide them in her

village. Despite listening to the broadcasts from

London, it is clear that the Jewish population of

Sighet had never heard or never seen any reason to

believe that Germany and its allies were following

a policy of physically exterminating the Jews of

Europe.

Mr.

Wiesel tells us that he was beaten twice by "Idek."

The first time, he was beaten for no reason at all.

The second time, he was beaten for discovering that

"Idek" had made his entire command work on Sunday,

apparently a standard day of rest for the prisoners

in the Buna complex, so that Idek could have a

sexual interlude with a Polish girl at the

factory.

Mr.

Wiesel tells us that he was beaten twice by "Idek."

The first time, he was beaten for no reason at all.

The second time, he was beaten for discovering that

"Idek" had made his entire command work on Sunday,

apparently a standard day of rest for the prisoners

in the Buna complex, so that Idek could have a

sexual interlude with a Polish girl at the

factory.