August 31, 1999

Evil

Isn't Banal Evil

Isn't Banal

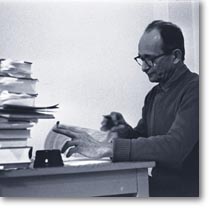

Eichmann

in his

prison cell, 1963 By RON ROSENBAUM EARLIER this month a

German newspaper published excerpts from

what were claimed to be "diaries" Adolf

Eichmann kept while awaiting trial in

Israel, in which Eichmann once again

reprised his deceitful "just following

orders" alibi for his key role in

expediting the Nazis' "Final Solution."

The Israeli government is debating whether

to release the full text of Eichmann's

jailhouse writings. So perhaps now is the time to put to

rest at last the intellectual rationale

that gave credibility to Eichmann's lie

about his role: the fashionable but

vacuous cliche about the "banality of

evil." It is remarkable how many people

mouth this phrase as if it were somehow a

sophisticated response to the death camps,

when in fact it is rather a sophisticated

form of denial: not denying the crime but

denying the full criminality of the

perpetrators. You're probably familiar with the

origin of the banality of evil: It was the

subtitle of Hannah Arendt's 1963

book "Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on

the Banality of Evil." The phrase was born

of Arendt's remarkable naiveté as a

journalist. Few would dispute her eminence

as a philosopher, but she was the world's

worst court reporter, someone who could be

put to shame by any veteran courthouse

scribe from a New York tabloid. It somehow didn't occur to Arendt that

a defendant like Eichmann, facing

execution if convicted, might lie on the

stand about his crimes and his motives.

Did she actually expect Eichmann to repeat

what he's reported to have said at the end

of the war: "I shall laugh

when I jump into the grave because of

the feeling that I killed five million

Jews"? In the absence of such an

admission, Arendt chose instead to take

the Nazi at his word when he took the

stand and testified that he really

didn't harbor any special animosity

toward Jews, that when it came to this

little business of exterminating the

Jews he was just a harried bureaucrat,

a paper shuffler "just following

orders" from above. Arendt then proceeded to make

Eichmann's disingenuous self-portrait the

basis for a sweeping generalization about

the nature of evil. It is a generalization

that suggests that conscious, willful,

knowing evil is irrelevant or virtually

non-existent; that the form evil most

often assumes - the form evil took in

Hitler's Germany - is that of faceless

little men following orders, and that

old-fashioned evil is the stuff of

childish fairytales. There are, of course, a few problems

with this analysis. Even if it were true

that Eichmann was just following orders,

someone had to be giving the orders. In

Eichmann's case, those orders came from

Reinhard Heydrich, a fanatical

hater who was relaying with enormous

enthusiasm the exterminationist orders of

Adolf Hitler. And as Daniel

Goldhagen noted in "Hitler's

Willing Executioners," a great many

ordinary Germans showed a great deal of

enthusiasm for the genocidal tasks to

which they had been assigned. It hardly needs to be said that Hitler

and Heydrich's hatred was not in any way

banal. It is closer to what Arendt herself

had previously called, in "The Origins of

Totalitarianism," "radical evil." In that

book, she wrote of the existence of an

"absolute evil" that could no longer be

understood and explained by the usual

motives of self-interest, greed,

covetousness, resentment, lust for power,

and cowardice, but of a "radical evil

difficult to conceive of even in the face

of its factual evidence." There was, in Arendt's initial response

to the death camps, a kind of philosophic

humility: Nazi evil was so radical, it was

difficult even "to conceive of." But the

humility disappeared in the Eichmann

reportage. She decided she had it all

figured out. "Evil is never radical," she

wrote to the philosopher Karl Jaspers,

"it's not inexplicable, it can be

understood, defined by the phrase the

banality of evil." Since then, the phrase "banality of

evil" has itself become one of the most

egregious instances of genuine banality in

our culture. For all its pretended

sophistication, it has the effect of

letting mass murderers off the hook. It

wasn't their fault so much as the social

conditioning that robbed them of the

ability to question immoral orders. The

new Eichmann excerpts attempt to blame his

"childhood discipline" for the acts he

committed as an adult. There is great comfort in abandoning

the "nightmare" of radical evil for the

notion of banality. But the plain fact is

that the Holocaust was committed by fully

responsible, fully engaged human beings,

and not by unthinking bureaucratic

automatons. The Nazis were human beings

capable of making moral choices who

consciously chose radical evil. This, the nightmare from which Arendt

fled, is the truth about the perpetrators

of the Final Solution. Banality plays no

part in it. Let's hope that the possible

surfacing of Eichmann's new "diaries" -

actually the same old fraudulent alibi

Arendt's bad reporting gave a fig leaf of

legitimacy to - can be the occasion to

bury the false consolation of that foolish

cliché. Mr. Rosenbaum

is author of "Explaining

Hitler"

(HarperCollins, 1999) and a columnist

for the New York Observer, in which an

earlier version of this article

appeared. [Eichmann

index] |