August 19, 1999

What

to do with Eichmann's memoirs? What

to do with Eichmann's memoirs?

By HERB KEINON A RENEWED interest in

the documents holed up in the state

archives has sparked a controversy over

who should publish the papers of the

arch-perpetrator of the Final Solution, in

what manner, and why. While sitting in the bowels of Israel's

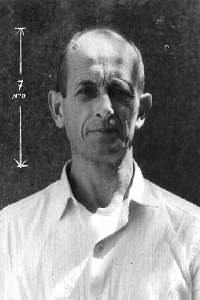

penal system, Adolf Eichmann -

arch-perpetrator of the Final Solution -

put pen to paper in 1961-1962 and wrote

memoirs spanning some 1,200 pages. Thirty-seven years later, these

memoirs, which then prime minister

David Ben-Gurion ordered buried in

the national archives, are at the center

of a debate: who should publish them, in

what manner, and why. "I am certainly in favor of publishing

the material," said Evyatar

Friesel, the Israel state archivist,

and one of just a handful of people to

have read the document in its entirety.

"It needs to be published as part of an

effort to publish all material on the

Holocaust." Eichmann was kidnapped from his refuge

in Argentina in 1960 and brought to

Israel, where he stood trial in Jerusalem

for crimes against humanity and the Jewish

people. He was found guilty in December

1961 and, after his appeal to the Supreme

Court was rejected, was hanged in May

1962. Ideally, said Friesel, a modern Jewish

history scholar, Eichmann's memoirs

"should be published in a scientific

manner, in their entirety and with

explanatory footnotes." But even if the material was not

prepared in this manner, it should still

be released, Friesel said. But Amos Hausner, the 49-year

old son of Gideon Hausner, the

former attorney-general who prosecuted

Eichmann, said the material should not be

published if not done so in the "proper

manner." HAUSNER said the document is a grossly

sanitized version of history that Eichmann

wrote to make himself look good and should

only be released if it is accompanied by

the trial's verdict and another document

in the archives - the Sassen document. The Sassen document is some 600 pages

of interviews Eichmann gave a Dutch Nazi

journalist named Willem Sassen in

1957, before his capture by Mossad agents,

in which he owned up to his role in the

extermination of Jews and expressed regret

that he was not more effective at his

job.[*] That document, written while he was

still free, is more honest than the one

written in jail, when Eichmann thought he

could influence the verdict, Hausner

said. The Eichmann memoirs, with which

Hausner is familiar through his father's

work, is merely a written justification of

the Nazi henchman's defense: that he was

just a small cog in a giant killing

machine, a mid-level bureaucrat merely

following orders. In many instances,

Hausner said, the memoir is full of

lies. "Eichmann's defense," said Hausner, "is

that he was just a small cog. If so,

according to this argument, then maybe we

should not have convicted him. His memoir

is an attempt to support this thesis." According to Hausner, a Jerusalem

lawyer best known for his work taking on

the country's tobacco industry as an

ardent anti-smoking advocate, if Israel

refused to publish the document, then

there could arise those claiming that the

country is trying to hide something. "That is the last thing we want," he

said. "But that does not have to lead us

to the other extreme, to take something

that we know in many cases is a lie, and

give it publicity." The solution, he said,

is to publish the document not as

something that stands alone, but rather

along with the Sasser document and the

verdict which will put the memoir in its

proper context. IT WAS Hausner's father, Gideon, who

convinced Ben-Gurion in 1962 to bury the

document in the state archives for 15

years. In the Hebrew edition of his book

on the trial,

Justice in

Jerusalem, Hausner writes that he

spoke to Ben-Gurion about the document. "I

said that his [Eichmann's] desire

to publish it at the same time that the

verdict was due to be released was an

attempt to compete with the verdict and

would raise doubts in the world about the

justice of the verdict. "Eichmann was given an opportunity to

express his opinion when he was on the

witness stand for 30 sessions. We are not

obligated to publicize his work and

circulate his false version - the law does

not obligate this, and there is no

justification for it. Ben-Gurion ruled

that it be filed away for 15 years." And so it was. Ben-Gurion's biographer,

Shabbtai Teveth, said Ben-Gurion's

decision was born of a feeling that by his

actions, Eichmann had forfeited his right

to express himself outside of the

court. "Ben-Gurion did not make a final

determination [on the matter],"

Teveth said. "He said, 'I am here in 1960,

and as long as I am here, it will not be

published. But I do not know what will be

in 15 years. Maybe in that time the whole

world will view Nazism as I see it.

Someone else will come in my place,

discuss the matter, and decide again.'

" Teveth disputed claims that Ben-Gurion

made his decision lest the document be

used by Holocaust deniers, saying the

issue was not something that greatly

concerned the prime minister. In fact, said Efraim Zuroff,

director of the Simon

Wiesenthal Center in Jerusalem, the

Holocaust deniers would have little use

for this document, since Eichmann admitted

that the extermination of Jews took place

and only denied that he had a key role in

it. "One of the interesting points is that

this document can be used against

Holocaust denial, because it is an example

of someone with such an important role

admitting to the Holocaust," Zuroff

said. According to Friesel, the issue of what

to do with the document was raised again

during prime minister Menachem

Begin's tenure, and at one time was

scheduled to be brought to the prime

minister for a decision. This was around

the time that Hausner published his book

in Hebrew and added material on the

little-known memoirs. The issue, however, never made it to

Begin's desk. "He had other things to deal with,"

said Friesel, the country's top archivist

for the last six years. The memoirs

remained on the shelf until two years ago,

when a German journalist asked to see the

document, and discussions about what to do

with it started anew. The discussions intensified earlier

this year after the screening of a movie

about Eichmann called The Specialist. Following that film, Friesel received a

number of requests from historians and

journalists to see the memoirs. News of

the existence of the memoirs was reported

in Germany, and one of Eichmann's four

sons, Dieter, decided to petition

Israel for the manuscript. This raised the

fear that he would then want to publish it

himself, thereby making money out of the

atrocities his father perpetuated,

something Hausner said would be

obscene. On Sunday, Attorney-General Elyakim

Rubinstein received a request from

Eichmann for the papers, and on Monday his

office released a statement saying that

the "inclination is to bring the material

to the public for its consideration as

soon as possible, by publishing it in its

entirety by German researchers, with

comments and appropriate accompanying

material." HOLOCAUST historian Yehuda

Bauer, while applauding decision to

publish the document because "we are under

a moral obligation not to hold back the

publication or accessibility of any

document relating to the Holocaust," added

that he would be "very surprised" if there

was anything new in the manuscript. But, he said, "it may be important from

the point of view of a psychological

investigation of a murderer's mind." Bauer, who once skimmed the document

for "a couple of hours," said he is "not

dying to read it, because I don't think

there is anything new in it." Bauer was involved in the recent

decision in the Justice Ministry to make

the document public and said he favors

letting German researchers prepare the

final, footnoted version of the text,

because "We don't have a group of people

specializing in the study of the

perpetrators in this country. In Germany,

there are a number of reputable and

excellent people who have done great work

on this and with whom we are in very

friendly contact. It has to be a

scientific publication and not a

sensationalist or commercial one. And it

must be stated quite clearly that this is

not at all done for profit." Another leading Holocaust historian,

Yisrael Gutman, editor-in-chief of

the Encyclopedia of

the Holocaust, said that although

he has known about the memoirs for years,

he never made an attempt to read them. "This is not one of those documents

that you say, 'If this appears, it will

place everything in a different

perspective,'" Gutman said. "I am much

less interested in what Eichmann thought

and what he told of himself, because he

did not have a great philosophical or

ideological position inside the Nazi

Party. What is of far more interest for us

is what Eichmann did." ©

1995-1999, The Jerusalem Post - All rights

reserved[Eichmann

index]

* Website note: The Sassen papers

(600 pages) which are referred to

appear to be the documents

deposited by David Irving in the

German Federal Archives in

1992.

|