| [David Irving's "Radical's

Diary" für Jan.: 28

| 31

| Feb: 1

| 2

| 3

| 5

| 7

| 8

| 10

| 15

| 16

| 17

| 20

|

24

| 28

| Mar: 1

| 2

| 6] London, Wednesday, April 11, 2000

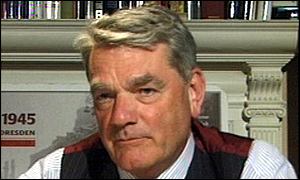

History needs David Irvings by Donald Cameron Watt The libel case brought by historical writer David Irving against Penguin Books and American academic Professor Deborah Lipstadt ends today. Professor Lipstadt had, so Mr Irving complained, accused him of being a "Holocaust denier", in the words of her counsel, "not a historian but a falsifier of history".

Eight months before the case came to court, The New York Times asked a number of leading American and British historians whether they regarded Irving as being a historian "of repute". The large majority of those polled, ranging from the ultra-conservative Right to the ex-communist Left, answered yes. Only those who identify with the victims of the Holocaust disagreed. For them Irving's views are blasphemous and put him on the same level of sin as advocates of paedophilia. In a number of countries "Holocaust denial" is a crime. In Britain and America pressure is brought on publishers not to print works embodying this version of history. Irving claimed the accusation to be a threat to his livelihood; he sought compensation; and he sought to silence his critics. Make no mistake, however. Both sides in this action were engaged in what that great historian R H Tawney once called "the gladiatorial school of historical controversy". Penguin was certainly out for blood. The firm has employed five historians, with two research assistants, for some considerable time to produce 750 pages of written testimony, querying and checking every document cited in Irving's books on Hitler. Show me one historian who has not broken into a cold sweat at the thought of undergoing similar treatment. For what it is worth, I admire some of Mr Irving's work as a historian. Thirty-five years ago I collaborated with him in the publication of a lengthy German intelligence document on British policy in the 12 months before the British declaration of war on Germany in September 1939. Ten years ago he published, on his own in German, a revised version of the book. From every point of view it was a considerable advance on the work I had collaborated on. He had found a lot more documents and had identified and inter-viewed a number of officers of the organisation in question. In the American archives he had found a lengthy post-war American evaluation of the organisation, incorporating a British intelligence document, which will now, we hope, be released to the Public Record Office. Irving's book, The Rise and Fall of the Luftwaffe, is still recommended by historians of the war in the air. That is one side of Irving. As a historian he betrays some of the characteristic faults of the self-taught. He refuses to look beyond the documentation. Like every victim of con-artistry he is beguiled rather than warned by evidence which seems to confirm his views. He can be seduced by the notion of conspiracies, to mislead, to cover up the misdeeds of the "good guys". He has a flair for self-publicity. He has also an encyclopaedic knowledge of the truly enormous mass of German documentation which fell into the hands of the victors in 1945. Moreover, his first book, on the bombing of Dresden, opened to him private papers, diaries and so on, previously unknown, of "respectable" German officials who had gone along with the Nazis. No book of his has ever failed to come up with new evidence. He has earned a considerable income from his books, especially since the first volume of his Hitler studies. He is translated into numerous languages. And he has taken up positions which have led to his being banned from entry into various countries. The defence made much of this in court. There are videos of him addressing neo-nationalist audiences in Germany - he speaks German fluently, having learned it as a steel worker before he began writing - in which he both looks and sounds uncannily like Hitler. Professional historians have been left uneasy by the whole business. Many distinguished British historians in the past, from Edward Gibbon's caricatures of early Christianity to AJP Taylor, are open to the accusation that they allowed their political agenda and views to influence their professional practice in the selection and interpretation of historical evidence. As for conspiracy theorists, I see that yet another book on "the Hess conspiracy" and yet another alleging that President Roosevelt had prior knowledge of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor are about to appear. There are prominent American academics whose careers suffered no setback despite their denying the scale and scope of Stalin's purges. All "round objects", of course, but I have not noticed any books attacking the perpetrators of such twaddle. The worst outcome of this case could be to drive the Holocaust denial school back into the depths from which Irving "outed it". The process has begun already with the circulation of a private newsletter soliciting support. This is how it used to be, with privately printed pamphlets arriving on one's desk in plain brown envelopes. There are always those who believe that what "they" won't let one read must be true. A lot of them work in the media. And any criminal nonsense can be defended by calling it "controversial". I know the Holocaust happened. I grew up among those who

were fortunate to escape it. But what happens when the

witnesses are all dead, if the reality has not been thrashed

out? The truth needs an Irving's challenges to keep it

alive. Professor Donald Cameron Watt is the author of How War Came; the Immediate origins of the Second World War (Heinemann 1989). He is the editor of Hitler's Mein Kampf (Pimlico 1991). | ||

London, April 11, 2000 |

"Holocaust

denial" is a clumsy term for those who deny that the

Holocaust, Hitler's deliberate attempt behind the cloak of

total war to exterminate the entire Jewish population of

Europe, happened, and alleges that the notorious "death

camps",

"Holocaust

denial" is a clumsy term for those who deny that the

Holocaust, Hitler's deliberate attempt behind the cloak of

total war to exterminate the entire Jewish population of

Europe, happened, and alleges that the notorious "death

camps",