|

David Irving reminisces

about working on IN THE MID-1960s, when I was beginning to work on the Hitler biography, with no funds to support the task, I had to take on literary odd jobs to support myself and young family -- Josephine was born in 1963, her sister Pilar the year after.

The memoirs were unexpectedly solid. I felt they were of historical importance, as they cast light into areas that only Keitel could know about; they were written not without remorse for his role in having allowed himself to be the co-signatory of some of the war's more questionable orders. Kimber offered me a flat fee of £200 to translate the book; not much money even in those days, but not chickenfeed either; and not having behind me a father who made his millions in the Kentucky Fried Chicken business, I could not sniff at any source of income. In fact my father, a naval officer who had written for Kimber's his memoirs of the great naval Battle of Jutland, in which he had fought in 1916, had recently passed away.

The translation was set up in galley proofs -- an important point -- when Kimber first read it. He noticed that a lot of stuff seemed to have been left out. There were ellipses . . . just about everywhere. He asked me to find out. I contacted the German editor, military historian Walter Görlitz; he confirmed that some passages had been left out of the German edition, as they were considered to be politically incorrect. Stuff like the entire Battle of Britain and so on. "The British are now our allies," he explained. This was not good. "Can we get them back, David?" asked Kimber, pouring more of his anemic China tea into the delicate porcelain cup he placed in front of me. "Would the family let us put it all back in, d'you think?" I knew that a daughter had married Field Marshal Werner von Blomberg's son. I located the field-marshal's son Karl-Heinz Keitel. He was living outside Cologne, and I arranged to visit him. The son had been a lieutenant colonel in the army. He was so delighted that an Englishman -- "the Englishman who wrote the first book about the destruction of Dresden" -- was prepared to go the extra mile and translate the Memoirs of Wilhelm Keitel in full, with all the "incorrect" stuff put back in, that he did four favours for me:

And finally,…

He spent the next ten years in Soviet gulags, and he is still alive today; he had never spoken to anybody about those times. "Otto -- this is David Irving. He wrote the book on Dresden." That was the introduction. He added that I was translating the field marshal's memoirs, in full, for the English. Günsche sat down and talked briefly, and a few days later he talked again for several hours into my tape recorder. I still have the reels of tape; or rather I had them until they were seized by the British authorities along with all my other possessions last May (2002). We shall now fight to get them back. But I digress. The Keitel Memoirs were published, and eventually I received my translator's fee. When I looked at the cheque from Kimber's it was not however for £200; it was £67 (around $100 now), as payment for some three months' work. Not much money, even in 1966. "Author's corrections," said Kimber with his bland, oh-so-English smile. He tapped the translation contract: see, the author is liable for all the costs for "author's corrections" amounting to over ten percent of the printing bill. Because of the substantial late "author's corrections" at galley-proof stage, -- namely the restoration of the missing passages at Kimber's request -- the setting bill had been increased by, yes, around £130.

To him it was almost a game. Of course, as the English say, it is not who wins that matters, it is how you play the game. There were two by-products of this unfortunate incident. As I left, I gently plucked off Kimber's desk the completed, bound, typescript of my next book The Knight's Move (later published in 1967 as The Destruction of Convoy PQ.17) and flounced out of his Knightsbridge office saying I did not intend to be "cheated" a second time. He sent his secretary Amy Howlett running out into Wilton Place after me, pleading for me to return the new manuscript. I stayed firm, and transferred the PQ.17 book to Cassell & Co Ltd: Cassell's and I were subsequently, in 1967, sued for the libel which Captain Jack E Broome, RN, alleged it contained: and we had damages and costs awarded against us amounting to a quarter of a million pounds or more in 1970. It nearly bankrupted the company, and did little to prosper my family's finances either.

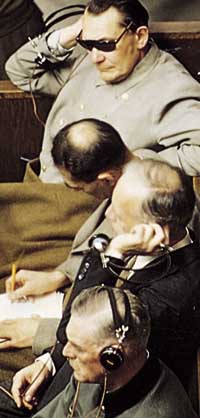

Photo above by Walter Frentz: Keitel, Göring, Dönitz, Himmler, Bormann |

My

publisher William Kimber asked me to draft a report

on the published death-cell memoirs of the chief of the

German high command, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel,

who had been hanged at Nuremberg in October 1946. They were

in German, but I had learned the language at school and as a

steelworker in the Ruhr (1959-60).

My

publisher William Kimber asked me to draft a report

on the published death-cell memoirs of the chief of the

German high command, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel,

who had been hanged at Nuremberg in October 1946. They were

in German, but I had learned the language at school and as a

steelworker in the Ruhr (1959-60). Not

really anticipating what an arduous task it is to turn out a

proper, literary, translation of a book (as opposed to the

kind of wooden-wordsludge that a Professor Richard

Evans calls a "translation") I accepted the task, and

many months later I turned in the finished typescript at

Kimber's Knightsbridge offices, in an old building where the

Berkeley Hotel now stands.

Not

really anticipating what an arduous task it is to turn out a

proper, literary, translation of a book (as opposed to the

kind of wooden-wordsludge that a Professor Richard

Evans calls a "translation") I accepted the task, and

many months later I turned in the finished typescript at

Kimber's Knightsbridge offices, in an old building where the

Berkeley Hotel now stands. On

that basis, I was lucky, I suppose, to have received

anything for my work at all, and not to have been presented

with a bill at the end of the job.

On

that basis, I was lucky, I suppose, to have received

anything for my work at all, and not to have been presented

with a bill at the end of the job.