If

someone worked at a Ford

plant, they made cars for a

living. If someone worked at

Sobibor, they killed Jews for

a living. If

someone worked at a Ford

plant, they made cars for a

living. If someone worked at

Sobibor, they killed Jews for

a living. --

Neal Sher, who headed

the OSI from 1982 to

1994.

--

Neal Sher, who headed

the OSI from 1982 to

1994.

|

Los Angeles, Saturday, July 14, 2001

COLUMN ONE Nazi

Saga Takes a New Turn By ERIC SLATER, Times Staff Writer CLEVELAND --

Twenty-four years ago this

summer, the U.S. Justice Department made a

remarkable allegation: One of World War

II's most notorious and malevolent

practitioners of genocide was not only

alive and well, he was living in

Cleveland. "Ivan the Terrible," the government

said, who drunkenly beat Jews as they

entered the gas chambers at Treblinka,

then turned on the gas himself before

heading out to rape local girls, now had a

wife, two children and a yellow-brick

house in the suburbs. He worked at the

Ford plant and went by the name John

Demjanjuk.

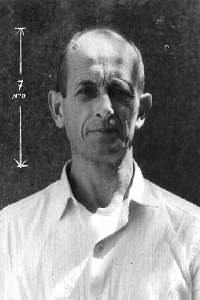

| Once

accused of being 'Ivan the

Terrible,' John Demjanjuk,

81, is now the target of renewed

U.S. efforts to deport and

denaturalize him. |

The government and its new Nazi-hunting

Office of Special Investigations, it would

turn out, had the wrong man.Yet 2 1/2 decades after the government

began pursuing him, eight years after

Israel's Supreme Court freed him from

death row when it became obvious the

Demjanjuk case had gone horribly awry, the

OSI is seeking once again to denaturalize

and deport him. Ivan "John" Demjanjuk, now 81, wasn't

Ivan the Terrible, government lawyers

acknowledge, and he probably was never at

Treblinka. But Demjanjuk, a Ukrainian farm

boy drafted by the Soviet army and quickly

wounded and captured by the Nazis, was

pressed into service as a guard at three

Nazi camps, government attorneys alleged

at a recent nonjury civil trial here. And

when he emigrated to the United States in

1948, the government says, he lied to

conceal that fact. Prosecutors have no witnesses placing

Demjanjuk at any of the camps, for he has

outlived most Jewish survivors as well as

any known guards. Prosecutors also allege

no specific criminal acts; courts have

ruled that a person who performed any duty

at a Nazi camp, willing or unwilling,

should be turned away at the U.S.

border. The OSI's case is based almost entirely

on a worn, yellowed identification card

issued by the Nazis to one Iwan Demjanjuk

and six other decades-old documents,

several of which were stored in secret

archives in the former Soviet Union and

discovered only after its breakup in

1991. Prosecutors say the paper trail shows

Demjanjuk served the Nazis at the

concentration camps Majdanek and

Flossenbürg and at the extermination

camp at Sobibor, Poland, where 250,000

Polish Jews were killed. Sobibor was a highly efficient killing

camp, the government and many historians

say, operated by just a few dozen members

of the SS overseeing 120 or so captured

Soviets ordered to serve as guards. Most

Jews were gassed the same day they

arrived. Anyone serving there in any

capacity at all, Jewish groups argue, has

much blood on his hands. "If someone

worked at a Ford plant, they made cars

for a living," said Neal Sher,

who headed the OSI from 1982 to 1994.

"If someone worked at Sobibor, they

killed Jews for a living." But Demjanjuk's defenders say the

documents underpinning the government's

case, which spell his surname four

different ways and were scattered across

two continents after the war, show little

other than that the OSI is again pursuing

the wrong man. And they contend the OSI--which was

found by the U.S. 6th Circuit Court of

Appeals to have "acted with reckless

disregard for the truth" in its first case

against Demjanjuk--is seeking not justice

but misplaced vengeance against an

octogenarian who, as a wounded POW, would

have had little say over his wartime role

anyway. "To go from Ivan the Terrible to

Ivan-the-Bad-Enough . . . I don't know why

[OSI] would want to do this,

especially considering what the court had

to say about their behavior in the first

trial," said Mark O'Connor, one of

the attorneys who represented Demjanjuk in

Israel. "I don't think it does justice to

the Holocaust, and certainly not to the

survivors." The latest case against Demjanjuk,

which is expected to be decided sometime

this summer by U.S. District Judge Paul

R. Matia, is part detective story,

part war story, and it is filled entirely

with death and grief. It is also likely to be the OSI's last

major effort against an alleged Nazi.

Organized in 1979 to hunt Axis war

criminals, the office is fast running out

of quarry. Meanwhile, Congress is

preparing to decide whether to continue

funding the office and expand its charter

to hunt modern-day war criminals. During the quarter-century the OSI has

pursued Demjanjuk, several hundred

suspected war criminals, from places

including Sierra Leone, Bosnia, El

Salvador and Rwanda, have settled in the

U.S. Some are alleged butchers who would

face reams of fresh evidence and dozens of

living witnesses should they be

prosecuted. For now, though, the government wants

John Demjanjuk. Dienstausweis, the folded paper card is

called, a service identity pass. It was

issued at the SS-run Trawniki Training

Camp to new arrival Iwan Demjanjuk, whose

boyish face is pictured in the upper

right-hand corner, in black and white. The

card lists his job as Wachmann, or guard;

his date and place of birth, father's

name, national origin (Ukraine) and a

physical description, including a scar not

unlike the one on the back of John

Demjanjuk of Cleveland. It also has the

holder's signature, in Cyrillic

script. The card indicates the new POW was

dispatched to Okzow, a Nazi-run farm, on

Sept. 22, 1942. On March 27, 1943, it

says, he was sent to work at Sobibor. The ID card, scrutinized and analyzed

down to the iron content of its purplish

ink, is the linchpin of the OSI's latest

case. But it is not new to the OSI.

Indeed, the Trawniki card was very nearly

the linchpin of the first case against

Demjanjuk. More than 20 years ago, the OSI was

prepared to argue essentially the same

case it has just presented here, with

fewer documents but potentially several

living witnesses. The primary allegation

then, as now, was to be that Demjanjuk

served as a low-level guard at Sobibor and

other camps--but not Treblinka--then lied

about that service upon entering the

U.S. Everything changed when an even darker

possibility arose: that the Cleveland auto

worker was not just another death camp

guard but rather someone who, even amid

the Nazi orgy of murder, managed to

distinguish himself as singularly

evil. The specter of Ivan Grozny arose

quite by accident. In 1976, before the birth of OSI, the

U.S. Immigration and Naturalization

Service mailed Israeli Nazi-hunters 17 mug

shots of suspected Nazi collaborators. The

INS was most interested in another

Ukrainian-born emigre, a man named

Feodor Fedorenko. Israeli

investigators happened to place

Demjanjuk's 1951 visa photo next to the

picture of Fedorenko. In a newspaper ad, the Israeli

government asked Treblinka survivors to

come view the photos to see if they could

identify any as their tormentors. Several

identified Fedorenko, who would later be

deported to the Soviet Union and

executed. Several others, however, were more

interested in photograph No. 16. That man,

they said, was the one they called "Ivan

Grozny," Polish for Ivan the Terrible.

That launched the case against

Demjanjuk. By the time of the first trial in 1981,

the brand new OSI was under tremendous

political pressure to prove its worth. And

it went forward with the Ivan the Terrible

case, despite growing misgivings among

some in the office. One of the reasons for doubt: By 1981,

the OSI had learned of a sworn deposition

given to the KGB in 1949 by another

Ukrainian, Ignat T. Danilchenko,

who was captured by the Nazis and said he

served with Demjanjuk not at Treblinka but

at Sobibor, Flossenbürg and a nearby

camp called Regensburg. The government

neither introduced the Danilchenko

"protocol" at trial nor turned it over to

the defense for six years. Demjanjuk's story, which has shifted

repeatedly over the years, though not as

much as the government's, was that he was

held in two POW camps after his capture

and then sent by the Germans to fight his

former army, the Soviets, with a band of

other Ukrainians in Austria. Never, he has

maintained, did he serve at a

concentration or extermination camp. U.S. District Judge Frank J.

Battisti didn't believe him. He

believed the survivors, who testified

emotionally about the evils committed by

Ivan the Terrible, the man they said sat

before them. In 1981, the judge stripped

Demjanjuk of his citizenship, and in 1986

he was deported--not to his home country

of the USSR, which likely would have

charged him with treason, but to Israel,

which would try him for war crimes.  The

trial was Israel's first against a Nazi

since 1962, when an unrepentant Adolf

Eichmann (right) was found guilty

and hanged for administering the

Holocaust. With Demjanjuk, soft-spoken and

ham-handed, described by prosecutors as

the devil in disguise, the trial served

not only as a Holocaust tutorial for a

generation of Jews born after the war but

also as a reminder of how many war

criminals continued to live freely. The

trial was Israel's first against a Nazi

since 1962, when an unrepentant Adolf

Eichmann (right) was found guilty

and hanged for administering the

Holocaust. With Demjanjuk, soft-spoken and

ham-handed, described by prosecutors as

the devil in disguise, the trial served

not only as a Holocaust tutorial for a

generation of Jews born after the war but

also as a reminder of how many war

criminals continued to live freely.

The Israeli tribunal found Demjanjuk

guilty and in 1988 sentenced him to die as

Eichmann died, at the end of a rope. Even as Demjanjuk's trial was winding

down, however, so too was the Soviet

Union. And from a Ukrainian state archive

emerged the depositions of 37 Treblinka

guards captured by the Red Army at the end

of the war. Every one of them identified

another man, Ivan Marchenko, as Ivan the

Terrible. It soon became clear that Demjanjuk was

almost certainly not Ivan the

Terrible. Israel's Supreme Court freed Demjanjuk

in 1993. In its decision, the court said

there was considerable evidence that

Demjanjuk was indeed a Nazi collaborator

who served at Majdanek, Flossenbürg

and Sobibor, but that since the

allegations were that he was Ivan of

Treblinka, he had not had a chance to

defend himself on these other

allegations. Prison workers were building his

gallows when the call came to set

Demjanjuk free. 'Forced

to Rely on Trial by

Archive'"The things we do in the name of

righteousness . . . historically have led

us down dangerous roads," said Michael

Tigar, a well-known Washington defense

attorney who is handling Demjanjuk's

latest case, free of charge. "Someone

needs to take a serious look at how these

cases are being done. With the deaths of

the live witnesses who can support or

contradict their version of events, the

government is increasingly forced to rely

on trial by archive." Indeed, the government's latest case is

almost entirely archival, and most of its

witnesses in the trial that ended in June

were experts who testified as to the

authenticity of the fragile documents--a

key point of dispute by the defense. Over the years, however, the archival

case against Demjanjuk has grown, ever so

slowly. At the same time, it has become

increasingly apparent that wherever and

however he spent the war, Demjanjuk has

never told the whole truth about it. In addition to the shrapnel scar on his

back, Demjanjuk, who fought successfully

to have his U.S. citizenship restored in

1998, has another notable scar, this one

on the inside of his upper left arm. He

created the scar himself, Demjanjuk

acknowledges, when he gouged out a

blood-type tattoo from the war. He said he

received the tattoo while fighting with

the German-sponsored Ukrainian unit in

Austria. There is little historical evidence

those fighters were tattooed, however,

while it is well documented that the SS

tattooed the blood types of many POW

conscripts on the upper left arm. Demjanjuk, at one point, claimed to

have been held at a POW camp in Chelm,

Poland, even after it had been overrun by

the Red Army. And he has offered various explanations

for why, on his visa application, he said

he lived in Sobibor, Poland, from 1936 to

1943. Before it became a death camp,

Sobibor was little more than a rail stop

that didn't even appear on most maps,

historians say. Prosecutors contend there was only one

explanation for why a former Ukrainian POW

would come up with the name Sobibor, and

that it is highly incriminating. "It would be like someone asking you,

'Where were you on Nov. 22, 1963?' and you

saying, 'Well, I happened to be in Dallas

that day, at the book depository, with a

rifle . . . [but] I'm not Lee

Harvey Oswald," said one government

official, who asked not to be

identified. While it has never been determined

whether the signature on the Trawniki card

belongs to Demjanjuk, he and his attorneys

have offered various theories as to the

card's authenticity. With the Soviet Union under attack in

the 1970s for its treatment of Jews, the

KGB may have forged the Trawniki card to

demonstrate its commitment to tracking

down those involved in the Holocaust,

Demjanjuk has suggested. In the most

recent trial, the defense argued that the

card was probably issued to Demjanjuk's

cousin, also named Ivan Demjanjuk, who

grew up in the same village, Dub

Macharenzi, in central Ukraine. The government, meanwhile, has

collected evidence in addition to the

Dienstausweis it says places him at two

concentration camps, including a

disciplinary report that turned up in a

Lithuanian government archive. Filled out

by an SS sergeant at the Majdanek

concentration camp on Jan. 20, 1943, the

report says Wachmann No. 1393, named

"Deminjuk," and another guard were given

25 lashes for leaving their posts to buy

onions and salt. OSI investigators discovered two

transfer rosters from Trawniki, both held

in Russian archives, one listing "Iwan

Demianiuk," the other "Iwan Demianjuk,"

both with ID No. 1393. They found a duty

roster from the Flossenburg camp and a

list of 117 Flossenburg guards in German

archives and indicating the presence of

guard No. 1393, "Demenjuk." And in German records they uncovered an

armory log from Flossenburg reporting the

issuance of a rifle and bayonet to

Wachmann "Demianiuk" on Oct. 8, 1943. "There can be no question," prosecutors

wrote in a trial brief, "that these seven

documents refer to Defendant." Thin

and Frail Now, He Rarely Leaves

HomeOnce the burly stereotype of a Rust

Belt auto worker, Demjanjuk is thin and

frail now, according to the few who have

have seen him in recent years. He seldom

leaves the yellow-brick house on the quiet

street where he lived before his first

trial and to which he returned after being

freed by Israel. He was expected to testify during his

trial but never appeared in court. His

attorney, Tigar, declined to say why. The

defense called only one witness,

Demjanjuk's son, John Jr., who was

11 when reporters and photographers filled

their frontyard on Aug. 25, 1977, asking

about Ivan the Terrible. Active in his

father's defense since his teens, John

Jr., now 35, testified for only a matter

of minutes, saying that in all his

conversations with his father, never had

the elder Demjanjuk told him he had aided

the Nazis. And then the defense rested its case.

Like that of the government, it is based

almost entirely on old papers. If Demjanjuk loses the denaturalization

case, he would face a deportation trial.

If he loses that, and is still alive, he

could theoretically face another war crime

trial in Israel. Sandra Coliver, head of the

Center for Justice and Accountability, a

group that tracks latter-day war

criminals, estimates that several hundred

have entered the U.S. in the last 25

years. There's an accused Serbian torture

expert and murderer living in Atlanta, she

says, an ex-member and alleged executioner

from former Chilean dictator Augusto

Pinochet's secret police in Miami. "We certainly endorse the principle

that responsibility is something you carry

for life," Coliver said of the OSI's

prosecution of Demjanjuk. "We also believe

that there are hundreds of war criminals

living in this country and wish they'd get

the same attention as Demjanjuk." During its 22 years, the OSI has helped

extradite 54 people. Most were low-level

concentration camp guards. Only two were accused of serving at

extermination camps whose sole purpose was

to kill Jews: Fedorenko, executed by the

Soviet Union in 1986, and Demjanjuk. "We will pursue these individuals into

old age, if necessary, to locations

thousands of miles from the scenes of the

crimes," said one Justice Department

official. "You won't get away with it."

Our

dossier on John Demjanjuk Our

dossier on John Demjanjuk-

-

|