October 31, 2001

http://www.boston.com/dailyglobe2/304/living/Incredible_journey+.shtml Incredible

journey From Misha

Defonseca's flight from Nazis to publication of her

memoir, life has been a battle against the odds

By David

Mehegan,

Globe Staff  T'S

an amazing story. But then, it's often said, all

Holocaust survivor stories are amazing. T'S

an amazing story. But then, it's often said, all

Holocaust survivor stories are amazing.

It starts in autumn 1941. A Belgian Jewish girl,

age 7, runs away from the family that took her in

when her parents were arrested by the Germans.

Determined to find her parents, she sets out on

foot toward the east. Over the next four years, she wanders through

Germany, Poland, and Ukraine, turning south through

Romania and the Balkans, hitching a boat to Italy,

then walking back to Belgium via France. For most of this time, the girl sleeps in

forests and is, for weeks at a stretch, fed and

protected by packs of friendly wolves. She joins

bands of partisans, sneaks into and out of the

Warsaw ghetto, witnesses the execution of children,

kills a German soldier with a pocket knife, and

finally has a happy reunion at war's end with her

Belgian foster grandfather. That's the story of Misha Levy Defonseca,

67, who today lives in Milford with her husband,

two dogs, and 23 cats. Her book, ''Misha: A Memoire

of the Holocaust Years,'' was published in 1997 by

tiny Mt. Ivy Press, owned by Jane Daniel of

Gloucester.  The

book drew high-profile endorsements by Leonard

P. Zakim, late director of the New England

Anti-Defamation

League (''a scary must-read for anyone

interested in the Holocaust'');

journalist/historian Padraig O'Malley; and Nobel

laureate Elie Wiesel (''very moving''). The

book drew high-profile endorsements by Leonard

P. Zakim, late director of the New England

Anti-Defamation

League (''a scary must-read for anyone

interested in the Holocaust'');

journalist/historian Padraig O'Malley; and Nobel

laureate Elie Wiesel (''very moving'').

Though it sold poorly in the United States,

''Misha'' was a surprise bestseller in France and

Italy, and aroused interest from Hollywood (Walt

Disney) and TV's Oprah Winfrey. But about a

year after it was published, everything froze when

Defonseca and coauthor Vera Lee sued the

publisher for breach of contract, claiming they

never got their share of overseas royalties and

that the book was never properly marketed in

America. There was a long and bitter battle. Last summer,

a Middlesex Superior Court jury found against the

publisher, awarding Defonseca and Lee a total of

$10.8 million. The legal quarrel has been complex

and very public. And it's not over -- a judge must

still review the appropriateness of the jury

award. Daniel, to this day, rejects all the allegations

made by the authors.  BUT what has gone almost unobserved is the

disquieting subtext of the tale: Can Defonseca's

story be believed?

BUT what has gone almost unobserved is the

disquieting subtext of the tale: Can Defonseca's

story be believed?

Two renowned Holocaust

scholars told the

Globe they do not believe her story. They say it's

impossible for one child to have been everywhere

she says she was, to have witnessed all she

did. Odder still, even her coauthor and publisher,

while they consider her a remarkable woman with a

compelling story, had their doubts. And they still

do. Misha, however, remains adamant. ''This is

fact, this is history,'' she says. The making of ''Misha'' is almost as curious as

the tale it tells. In the mid-1990s, Jane Daniel,

then living in Newton, was doing public relations

for ''Play It Again Video'' of Needham, which makes

keepsake tapes from family photos. The owner's most memorable customer was a woman

who had ordered a two-hour video made about her

late dog, Jimmy. The woman was Misha Defonseca. When Daniel heard about Defonseca's childhood

odyssey, she smelled a book for her fledgling

publishing business. She met with Defonseca and her

husband, Maurice, to pitch the idea. Daniel

says Defonseca was reluctant at first, but

eventually warmed to the idea: ''First she said it

would be very painful,'' the publisher said in a

telephone interview, ''and then she said she would

like to do it for her son.'' Defonseca's spoken English is clear (she and her

husband came to the States in 1988), but she is no

author -- someone would have to help turn a

collection of memories into a book. Daniel

recruited her neighbor and longtime friend, Vera

Lee. A French specialist, Lee was a former professor

of romance languages at Boston College and former

director of Boston's French Library. Like

Defonseca, Lee says she was reluctant at first, but

agreed after her friend ''said I was the only one

she could trust.'' Lee and Defonseca set to work in 1995. ''We did

a lot of talking,'' Lee said during an interview at

her home with her and Defonseca. Misha's

experiences had happened ''over 50 years ago and she had some

very vivid recollections of certain episodes and

scenes, but naturally there were certain

loopholes. I was trying to piece it together in

a way that was as true to life as possible. In

other word, there had to be transitions: She

went to a country, we had to know how did she

get to the next one? How did she do her

traveling?''So I would write and bring it back to Misha

and very often it would jog her memory. This was

a child -- she was not going to have an exact

memory of every single thing that happened, yet

you had to make a book. And it had to be true to

Misha.'' Lee says she would write as many as three

versions of a chapter, take them to Daniel, they

would pore over them together, revise them further,

then Lee would bring one back to Defonseca. ''I speak French,'' Defonseca says. ''Vera has a

tape and she [makes] notes and I tell her

the story. And then she brings me the manuscript, I

correct and send it back to her. And for me it was

a very difficult thing. I had no understanding that

she had not been through [experiences such

as] this. And for her it was difficult.'' Indeed, Lee says that listening to Defonseca's

story was often wrenching. To grasp it, she would

try to experience things directly. ''At one point,

[Misha] ate mud,'' she says, ''and I went

out and ate mud to see how it would taste.'' To imagine what it must have been like to climb

a wall out of the Warsaw Ghetto, which the book

describes, ''I was trying to climb this brick wall

in front of my neighbor's. I really wanted to

understand what she was thinking. She wanted me to

taste raw meat, which I did after she assured me it

was from Bread and Circus.'' Differences

of opinion Daniel began to take a more active writing role,

showing the result to Lee. Their disagreements

grew. Lee says Daniel wanted the book longer and

wanted more sentimental and emotional content. She

says she wanted Misha to be in love with somebody,

for there to be a romantic twist to the tale. ''Misha objected to this,'' Lee says, ''this

wasn't the way it was at all, but the publisher

wanted this love interest. On every page, I would

say 'not Misha, not Misha,' but she would keep it

in.'' The friction came to a climax in 1996 when

Daniel gave Lee a choice of being paid for what she

had done thus far, or taking all of her work out of

the book. Lee refused the choice and began to talk

to a lawyer. Lee says Daniel tried to turn

Defonseca against the coauthor, a complaint Daniel

dismisses as petty. What is not in dispute is that Daniel took over

the writing and rewriting, and published the book

with only Defonseca's name on the cover. Daniel

furiously denies all the allegations made by Lee

and DeFonseca. She says she intervened in the

manuscript to save the project. She maintained in

court motions that the manuscript Lee turned in

''contained numerous historical errors ... and the

style of writing was too juvenile.'' It also came in late, and was much shorter than

promised, she alleged. As for the claim that Mt.

Ivy shortchanged Lee and Defonseca on royalties,

she insists, ''The weight of the evidence does not

support the jury's findings.'' She said the handling of the overseas royalties

conformed to standard publishing practices. ''There

was not a dime that was not accounted for,'' she

said. That there was money to fence over at all is

a tribute to the book's remarkable overseas

success. Though Defonseca got TV and newspaper feature

attention, the book got few if any American

reviews. But Boston literary agent Ike Williams

(then head of Boston's Palmer & Dodge literary

agency, since shifted to Hill & Barlow),

representing Mt. Ivy, and Lee and Defonseca for

foreign print and film rights, had good success

overseas. The French version, by Editions Laffont, sold

more then 30,000 copies, and the Italian edition,

published by Longanesi, sold more than 37,000.

There were also Dutch and Japanese editions, and

rights were sold to the German publisher Verlag

[sic], though

apparently the book never made it into print

there. Defonseca had a triumphant French tour, with

readings and TV appearances. Hollywood

calls Poor US sales notwithstanding -- about 5,000

copies were sold -- the outlook was bright for

other media. Walt Disney studios paid for a

six-month option on a movie, and there were feelers

from other movie producers, including Universal

Pictures and Henson Productions, as well as a

French filmmaker, Marne Productions. There was television: Defonseca was taped

frolicking with wolves at Wolf Park, an Ipswich

animal park, by a crew from Oprah Winfrey's

program. There were also inquiries from ''20/20''

and ''60 Minutes.'' When Defonseca and Lee filed suit in May 1998,

this interest faded. The Winfrey segment never

aired. The book, ''Misha: A Memoire of the

Holocaust Years'' is as real as those who created

it and quarreled over it. But lost in the conflict

is the question of whether the events it purports

to narrate are fact or fiction. The book was not unknown to Holocaust scholars,

in addition to Wiesel, even before it appeared. ''It's preposterous,'' says Lawrence L.

Langer of Newton, author of numerous books on

the Holocaust and considered by many the preeminent

authority on survivor narratives. Langer says a

woman -- he can't remember who -- called him about

''Misha'' to get his view of it. ''She sketched the story and I said, 'Don't do

it,''' he recalls. ''She said, 'Why not?' I said,

'because it isn't true.' I said, 'Ask her how she

crossed the Rhine, in the middle of the war, when

the SS is guarding the bridges at both ends. Find

the Elbe on a map and ask how a little girl goes

across that river. She speaks no German, she's

Jewish, poorly dressed, and no one says, 'Who are

you, little girl?' I said it's a bad idea, don't do it,

it will prove an

embarrassment.''

I said it's a bad idea, don't do it,

it will prove an

embarrassment.'' Daniel remembers sending the manuscript to

Langer, but not the telephone call. Langer says he

also discussed the story with Vermont-based

historian Raul Hilberg, author of ''The

Destruction of the European Jews,'' and Hilberg

(left) also thought it

impossible. Consulted by phone for this story,

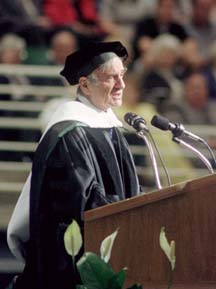

Hilberg reiterated his disbelief. Boston University professor Wiesel, who

blurbed the book

(left), was in Israel

as this story was written and efforts to reach him

through his staff have been unsuccessful. During an

interview with the Globe,  Defonseca

affirmed the truth of her story. Indeed, she said

she had recorded it before. Defonseca

affirmed the truth of her story. Indeed, she said

she had recorded it before. She repeated the story in her book about how,

when she was taken in by two single women after the

war, she wrote an account of her odyssey, but the

women did not believe it and forced her to burn it.

However, she added that she had written it all down

again in a diary that she began to keep in her

teens. After the French version of her book

appeared, ''the French book was so much my real

story, the way I am, that I don't need all these

fragments and papers. I

burned them in a

ceremony because, for me, it was

accomplished.'' Listening to this, Lee appeared to be surprised.

When asked if she had used these diaries in

preparing the book, she said, ''I didn't know they

existed.'' In fact, Lee herself was uneasy from the start,

especially about Defonseca's way of remembering --

later -- solutions to inconsistencies the

interviewer would point out. ''There were doubts,''

she says, ''but so much seemed credible that I

couldn't just throw doubt on the whole thing.'' Fact or

fiction? Still, she was worried enough to call an

official (she can't remember his name) of Facing

History and Ourselves, the national organization

that teaches the Holocaust and its lessons in

schools. She recalls the official told her that if

he were her, '''I would not write that, because

it's impossible,' and I went back to the publisher

and said, 'Do you see a problem?' And she said,

'Don't worry. These are the memoirs of a

child.''' Daniel herself became nervous in 1999, when

''Fragments,'' a prize-winning Holocaust memoir by

Swiss musician Binjamin

Wilkomirski, was proved to be a fake. ''It

sent a shudder through the industry,'' Daniel says.

''Up until then, publishers had never been called

upon to vet their stories'' to ensure their

accuracy. To be on the safe side, she put a defensive memo

''From the publisher'' on the Mt. Ivy Web site. It

listed several reasons why Defonseca's story could

be true, but then said, ''Is Misha's story fact

or invention? Without hard evidence one way or

the other, questions will always remain.''

Daniel now says, ''I have no idea whether it is

true or not. My experience is

that all Holocaust stories are far-fetched.

All survivor stories are miracles.'' Holocaust historians, of course, believe it

matters a great deal whether a memoir is true.

''Truth matters where the Holocaust is concerned,''

Langer says. ''I have spent years interviewing

Holocaust survivors. If people start making up

stories, it may make [real witnesses] doubt

their memories. It feeds ammunition to the

skeptical: that everyone exaggerates. But that's

not true.'' Misha Defonseca makes a compelling impression,

and does not sound like an untruthful person. Asked

why she thinks people are skeptical of her story,

she says, ''Because it is with animals. People are

afraid of animals.'' She says she hopes that now that the court has

returned all rights to the book to her and to Lee

that she will win for it a new and larger American

audience. She also still hopes for a movie deal,

thinking that somehow her story will reconnect her

with the family she lost so long ago. ''If there is a movie,'' she says, ''maybe

someone can see it and say, 'I know her parents.'''

Meanwhile, the other principals to this saga have

moved on. Lee is working on a new book about

American popular music. Daniel says she has lost

faith in the legal system, and has no plans for new

book projects. ''I am burned on publishing right

now,'' she says. ''I think I'm out of the book

business.'' © Copyright 2001

Globe Newspaper Company. Related items on this website:  New York Times: A

Bear-Faced Lie? Time 'Too Painful' to

Remember

New York Times: A

Bear-Faced Lie? Time 'Too Painful' to

Remember Index to the

Benjamin Wilkomirski lies

Index to the

Benjamin Wilkomirski lies Auschwitz index

Auschwitz index

|